The Story of the

Boston Musical Instrument Company

and the horns that made and broke it.

The Boston Musical Instrument Company began as the workshop of Samuel Graves around 1820. Graves and Co. consisted of Samuel Graves and his two sons William and George. In 1837, James Keat, son and student of English keyed bugle master Samuel Keat, joined the firm and steered it into the production of keyed bugles and related brass instruments. In 1841, Elbridge G. Wright established a firm at 71 Sudbury Street on the corner of Hawkins street in Boston, which was somewhere in the vicinity of the Boston Cable studios, downtown police station and city hall complex along New Sudbury street today. Wright was previously employed at the Graves shop.

The early work of both Graves and Wright was keyed bugles and saxhorns. The term saxhorn, used for a wide variety of families of chromatic brass instruments that produce tone from a cup mouthpiece, was as much the result of marketing as actual merit. By the time Sax was born in 1814, keyed bugles had been in production for some time. That same year Heinrich Stölzel and Friedrich Blühmel invented a bottom-coupled piston valve for use in making brass instruments known as the Stotzel valve. In 1838, when Sax was 24, the Perinet angled-port piston valve, based on the slightly earlier Berliner straight-through piston, was invented and within the same year Gustave August Besson had produced his first piston valve cornet in the form still recognized today. Sax did not begin building valved horns until 1844. Through skilled manipulation of the French patent system, Sax was able to over-generally claim proprietary rights to all valved brass instruments and in 1854, defeated Besson in a lawsuit. This resulted in the Besson firm moving to England (his wife then restarted the firm in Paris in defiance of Sax creating two Besson companies in different countries).

In the United States, Boston was the first brass instrument center, with firms such as that of band leader and cornetist David C. Hall opening up before the Civil War and incorporating in 1862. Both Graves and Wright transitioned to rotary valve brass instruments in place of keyed bugles as the technology spread in the 1840s. Graves would experience frequent financial stresses, but his former pupil Wright often accommodated him with access to tools, space and labor. There are many Graves & Co. horns engraved with “Made by Graves & Co. in the factory of E.G.Wright”.

D.C. Hall Band Instruments, across the street from Wright, also experienced the financial woes of early instrument makers and took on two partners, the Quinby brothers, in 1866 to become Quinby & Hall. Likewise, Wright had sold an interest in his firm to two others, Louis Hartman and the master maker of the future firm, Henry Esbach. Esbach had apprenticed to his father Heinrich Esbach in Germany before continuing to learn as an employee of Wright with frequent access to Graves. It was Hartman and Esbach who, seeing the frequent teaming of the two firms, instigated the merger of E.G. Wright & Co. with Graves & Co. While Graves and his sons appear to have favored the plan, Wright was enraged and, unable to stop the deal, left the firm and joined their cross-road rival changing its name to Hall, Quinby, Wright in 1869. The firm of E.G. Wright then became the Boston Musical Instrument Manufactory and proclaimed their E.G.Wright heritage not only on the cover of their debut catalog, but within an introduction that cautioned the reader against other “inferior” instruments bearing Wright’s name. Instruments in the Stearns Collection match those in the 1869 catalog, strongly suggesting that the new Boston company was indeed still building the same instruments as had been sold under Wright’s name.

While Wright died in 1871, causing the firm across the street to change names again to Hall & Quinby, the link between the firms that shared resources, particularly labor as workload fluctuated, would endure through their histories. Hall left his firm in 1876 and it became Quinby Brothers, which failed and was bought by music publisher Thompson & Odell in 1884 to expand their interests vertically. Known as the Standard Band Instrument Company, that firm floundered between 1894 and 1899 until the Vega Banjo Company eventually contributed enough capital to stabilize it. In 1909, Vega folded Standard into the firm as a division. They would remain in the business until after World War II, when they reverted to banjos exclusively.

Thus the Boston Company emerged into the fledgling American band instrument industry in 1869 just as the returning Civil War soldiers, who had known bands in almost every Northern and a third of all Southern regiments returned home and started up or expanded town bands. The Concert Band became the popular music of the later 19th century and the cornet was its star. Boston initially built several lines of brass band instruments with different bell orientations for concert and marching, but, as proclaimed in their first catalog, adhered primarily to rotary valves, claiming them to be superior to pistons.

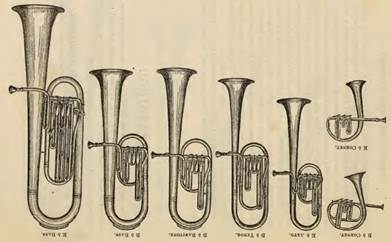

Above are the primary lines of brass band instruments offered in the first Boston catalog in 1869. These included the “Improved Design” instruments ranging from alto to bass which were meant to be complimented by the specialty line of trombones, valve trombone, French horn and the premium cornets and alto cornet that will be pictured on the next page. Marching lines included upright bell horns from soprano cornet to bass and a matching line of military style over-the-shoulders.

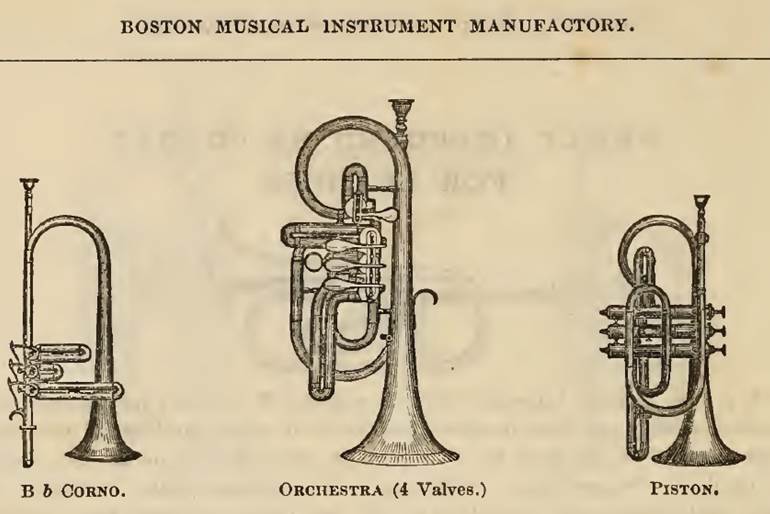

The premium cornets, the real flagship products of the original Boston firm included only one Perinet valve cornet in concession to the growing popularity of these valves. (See below)

Below is the bell marking of an 1883 Boston cornet showing the first name of the company, the Boston Musical Instrument Manufactory and the 71 Sudbury Street address.

Esbach, Hartman and William Reed, the other owners of Boston, were determined to become the first premium American instrument maker. At the time, the artist market was dominated by two French firms. The first was Antoine Courtois, the oldest brass instrument company that survives today, having been founded in 1789 and a maker of brass instruments for the army of Napoleon. The second was Fontaine-Besson, the French restoration of G.A. Besson’s firm.

In the 1870s Boston produced several “Two Star” cornets with rotary valves that were some of Esbach’s best work. While well received, the leading artists of the day, cornet players being the rock stars of that era, did not typically use rotary valves. One may surmise that linkages and difficulty in lubricating these valves made them something a virtuoso player did not want to bother with. The target market preferred pistons. In 1880, Henry Esbach’s crowning achievement, the Boston Three-star piston valve cornet was released.

The example above was made in 1883. The small rotary valve allows for keying the cornet in B-flat or A and the horn has only one shank for the mouthpiece. This was a quick-change model, but most of this period were sold with a standard tuning slide and the two shanks for A & B-flat. 1883 saw an apprentice at the Boston firm, James Warren York, a native of Grand Rapids, strike out on his own in two short-lived partnerships and then under his own name. The firm JW York and Son would be a major name in particularly low brass, with the Kanstul firm recreating famed early York low brass to this day.

The goal of achieving status equal to that of the French firms was attained in 1884 when a young new superstar by the name of Herbert L. Clarke decided to end his exclusive relationship with the governmentally sponsored band in Toronto in which he had learned to play following his brother, and thus had to surrender the Canadian Government’s Courtois on which he had been performing. He opted to buy a Boston Three-star to begin his freelance career as a featured star cornetist. It would be one of a very few instruments that he would actually pay for in his career. The majority of those he later played on from C.G. Conn, Holton and others were horns that he was paid to take.

This established Boston as the premier American maker and the design of the Three-star with its Besson-like, and even more Courtois-like, wrap and distinctive wishbone double spit key, as the preferred form of the cornet for the next two decades.

The Three-star cornet would remain in production for the following 34 years unchanged. Below is a 1908 example which bears the post-1902 name of the firm “Boston Musical Instrument Company”.

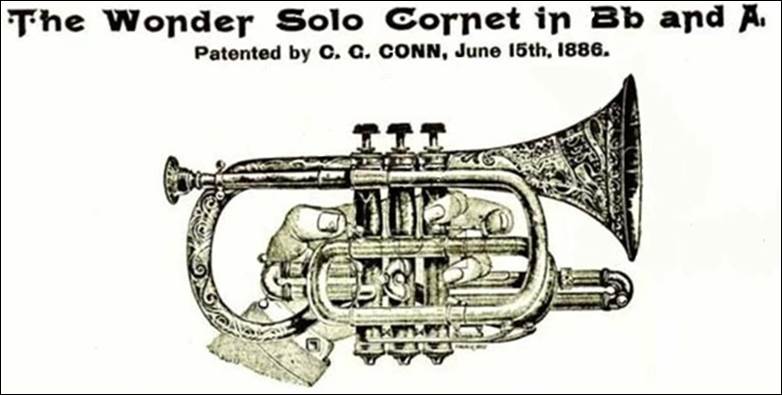

As the horn to beat, the design was, of course, quickly copied. When C.G. Conn introduced the “Conn Wonder Solo Cornet” in 1886 to replace the “4-in-One Cornet” on which the 1876 firm had been built, it was strikingly similar to the Boston design and helped Conn become the largest maker in the world.

Even including the wishbone spit key, the Wonder was clearly Conn’s attempt to match the Boston design in both tone and function, but with a few added features such as the reversed construction tuning slide and finger buttons to help adjust tuning on-the-fly for certain problematic pitches.

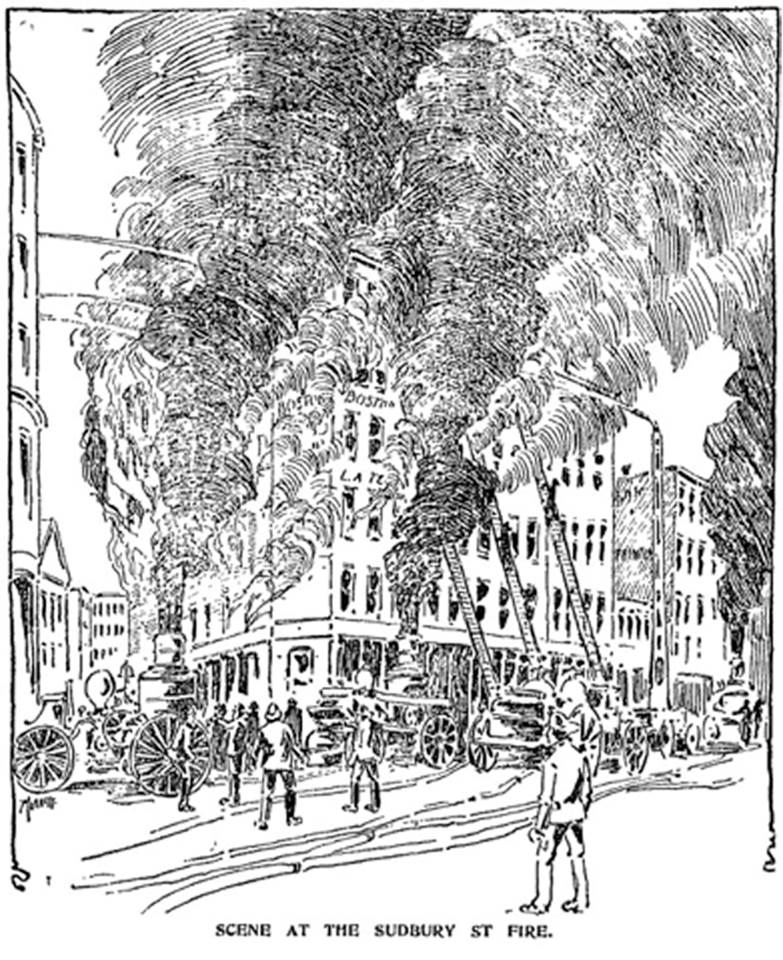

In 1899, the firm suffered a major set-back that turned out to be a wind-fall. The factory was located on the fourth floor of an older six story block that caught fire on July sixth. There were abundant supplies of machining oil and naphtha for cleaning throughout the building and the top two floors were filled with tobacco. The resulting fire completely destroyed both facilities and stock, but the firm was over-insured.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the market and technology both changed, while the Boston firm remained stubbornly committed to the unaltered form of the Three-star as its flagship. Relocated to 51 Chardon street, Boston sales declined sharply in the face of new instruments such as the Holton New Proportion and Couturier models as well as Conn’s Perfected Wonder with it’s Courtois inspired S-curve leadpipe design. The King Long Model cornets and York’s Perfectone that resembled an industrial piping accident as well as the Conn Perfected Wonder becoming the most imitated cornet of all time in the low-cost store stencil market all marked a movement to bigger, more powerful cornets as new generations sought to reinvent the stale popular music of their parents.

In 1902 Henry Esbach died, followed the next year by Louis Hartman, heir to his share in the firm. George Gale, the father in law of the surviving partner William Reed, took control in 1904 and took the firm public in 1913 to raise capital. Upon his death in 1916, his son Willard took the President’s chair, but turned control over to an experienced restaurant manager, Charles R. Harris. The disruption of World War One prompted the sale of the company to Cundy-Bettony publishing. By the time George Gale died, the oldest craftsmen in the firm had spent the last 36 years learning how to copy the master’s design, but not how to innovate new and better product. Without that knowledge, they turned to imitating an S-curve design, but not the Perfected Wonder (by then replaced by the Circus Bore model following the destruction and rebuilding of Conn’s factory in 1910-11). Instead they copied another such design being considered by J.W. York in Grand Rapids and which shortly thereafter became a common style among very cheap stencil horns. Below is a Boston Three-star cornet as it appeared in 1916.

Still bearing the three stars and the “Ne Plus Ultra” inscription of the 1880 model, its gold trim and detailing all mark it as a top of the line professional instrument. It produces a large, full cornet tone easily the equal of the PerfectedWonder, however its intonation is sub-par. By the teens, instrument makers had learned a great deal about nodal science and acoustics and were able to build horns, at least those at a top price point, to a much higher standard of quality.

The horn did not restore Boston’s plummeting sales and embodies the decline of the company from world class in 1880 to a second rate manufacturer. It failed firstly because of the visual association with inexpensive low quality horns. It failed to overcome that by attracting knowledgeable buyers because of its failure to play at the level demanded in that market. Finally, it failed because of a fundamental change in the market that made cornets obsolete as a flagship product to represent the corporate image that took place just a couple years after this example was built.

Following the 1909 absorption of DC Hall’s company into Vega, they began to build several tight, bright trumpet models such as the Chas E. George model named for one of their executives. In Chicago, by 1913 the small firm of Harry B. Jay was building it’s Columbia trumpet incorporating an unbraced half-reversed tuning slide that it had patented in 1907 in spite of the many earlier Conn horns with reversed construction. In 1917, three years into Boston’s attempt to reinvent themselves, the Frank Holton Company, also still in Chicago at that time, was the first to hire a trumpet player instead of a cornetist to be the spokesman for their products. They chose an Austrian refugee, who had changed his name and fled from England where he was performing in 1914, because he was a reserve member of the Austrian military on enemy soil when World War One began, by the name of Vincent Bach.

What was happening in Chicago was the vanguard of a global shift in popular music. By the teens, the concert band was no longer popular music, but rather the genre of an older generation. The clubs of Chicago were filled with the sounds of Swing and Jazz. Jay’s design concepts would be closely imitated by Holton in 1921 after their move to Elkhorn Wisconsin and would mark the split between the two families of trumpets today – those of the Bach/Besson style with heavier construction and standard braced tuning slides used in the orchestral and solo fields, and those of lighter construction with half-reversed unbraced tuning slides used in the dance and studio markets. The changing music of the day called for trumpets and those who provided the best such as Holton, Conn, King, Martin, Buescher, and eventually Bach himself, became the dominant band instrument makers.

The key moment when this change swept the industry is generally seen as one of the most bizarre moments in military history. In 1918, General Blackjack Pershing, commander of US forces Europe, commanded a massive force of draftee soldiers with an almost unlimited supply of weapons. Amazingly, he found himself unable to work with his counterparts that desperately needed his resources because of a cultural bias. European cultures of the prior century had been very imperialistic, militaristic and focused on pageantry that embodied their powerful national self-images. When Pershing arrived with only a handful of rag-tag Civil War style ad-hoc ensembles, the Europeans on both sides, who had come to see their large military and civic bands with equally pretentiously ornamented massive looking and sounding brass instruments as the embodiment of that identity, treated Pershing and the US forces with dismissive contempt. Pershing was forced to take time away from fighting the war in order to restructure military music with Congressional approval. He added 20 new bands, doubled the size of all bands, freed players of all other duties (like fighting – what an incentive to practice!), and added saxophones and trumpets to the concert band instrumentation to allow these bands to serve a morale function playing popular music when not impressing the natives. Returning soldiers came home with a new concept of the concert band and a taste for music that featured trumpets, not cornets, in the lead.

While Vega had recognized the need to sell trumpets early, their trumpets were not of the same quality as those from the aforementioned makers. They were smaller and weaker and very brash when pushed. The Boston company had built trumpets that were little more than stretched cornets as early as the 1880s, but had never put any effort into producing one that was of any quality or market appeal until after George Gale died. Under the new management, the redesigned Three-star cornet was still the lead product, but Boston also introduced a trumpet into this market - however one designed by a firm with no experience in the modern form of the instrument. Below is a 1917 “Boss-Tone” trumpet.

Boston advertising for these two last-ditch attempts to recapture their former market is below.

By the end of the war, with the financial impact of men and material having been repurposed away from them for the war effort, and the steady departure of the experienced workforce, Cundy-Bettony appears to have turned to stenciling or perhaps at first doing just final assembly of a horn built from outsourced parts. The Model-11 3-star trumpet below from the 1920s is such a product.

While it carries the three stars and characteristic Boston nibs on the valve slides, all of the other trim is no longer Boston in nature. The escutcheons that appeared on the earlier Boss-Tone are now complimented by non-Boston ferrules and other generic details that could have been made in a parts shop anywhere. The serial number, however, is still within the end of the Boston sequence and is imprinted on the front of second valve, lower, but still in keeping with Boston tradition.

This may have been a transitional horn. It appears that by the end, Boston turned to stenciling entirely in a final attempt to bring a viable lead product to market under the Boston name.

The Boston trumpet above was made sometime in the late 1920s, but contrary to the claim on the bell, was probably not made directly by Boston employees. While it features many Boston details, the overall design is very similar to that of the second-tier horns built by their longtime neighbor Vega. Boston horns always carried serial numbers on the second valve casing and numbered the casings as well 1,2,3. This horn has no serial number and the casings are numbered in the European style with high double digit numbers corresponding to dies. Such markings were common on horns made by Bohemian stencil fabricators, although the casings themselves also bear striking resemblance to Buescher valves, which were commonly sold to other makers.

One notable feature of these last two horns is that they include Henry Esbach’s greatest contribution to trumpet design – the nested sequential slides. In 1889 Esbach patented the concept of nesting the tuning slide inside of a second pair of sleeves that were connected by a brace in a H form. This rear slide would then be travel-limited by a stop rod like those used by Conn, Buescher, and Holton, or, as on this horn as well as those from Vega, Martin, and King, by a retaining ring catching an increase in tubing diameter. This provided a quick-change from B-flat to A and back without the need for a rotary valve or a second loop of tubing to provide a second slide as Besson had pioneered in 1867. This feature would be used by every maker of the early 20th century and lasted until music publishers made the A trumpet extinct after World War II.

The Boston company, either through greed or arrogance, never opted to reinvest profits from their greatest success, the 1880 Three-star, into developing new technologies and better product. They wrongly believed in the unending supremacy of their design and the ability to pocket its earnings without any expensive research and development programs. By the time the new owners attempted to right that mistake, the combination of limited talent and a fundamental change in the market doomed Boston to ever shrinking sales. When the Great Depression dawned in 1928, Cundy-Bettony elected, despite tremendous investment, to cut their losses and shut-down the Boston brand. It is unlikely that there was any actual Boston manufacturing still taking place by that time. The firm was officially dissolved March 23rd, 1955 after being idle for 27 years.

Compiled by Ron Berndt, October 2015