C.G. Conn and the Conn Band Instrument Companies

Ron Berndt, Memorial Day, 2016

Conn s Family and beginnings

The story of the Conn-Selmer division of Steinway Musical Instruments begins with the story of Charles Gerhard Conn and his family.

C.G. Conn was born in Phelps, in Ontario County New York on the 29th of January 1844. His father, Charles J Conn, was a life-long New York resident. Grandfather James Conn was also a New Yorker of Irish descent. Conn s mother, Sarah Benjamin, ultimately had four children, two boys and two girls, of whom Charles and one sister remained alive by 1893 when the family story was included in the Goodspeed Brothers Pictorial and Biographical Memoirs of Elkhart and St. Joseph Counties Indiana.

In 1850, the family relocated to St. Joseph Michigan where Charles J. engaged in farming briefly before moving again in 1851 to Elkhart Indiana to become a school superintendent. Charles G. spent his youth as a student in the local schools, obtaining a reasonably good basic education to compliment what his father s experience in farming could also teach. During this time, Charles learned to play multiple instruments and read music.

Conn s father spent the remainder of his career as an educator in Elkhart and for three years in LaPorte until hearing loss forced his retirement in 1876. Experimenting with photography in retirement, Charles J. Conn died in 1888, the year after Sarah passed away. Between the time of his father s retirement and his mother s death, Charles G. built a small instrument making venture into a large manufacturing concern, buying the Fiske company as a second manufacturing facility around the time of his mother s last Christmas.

But first, C.G. Conn had two other careers to experience along the way.

Conn s first and life-long avocation, the military

At the age of 17, with the US Civil War having begun, Conn enlisted on the 18th of May 1861 in the 15th Indiana Volunteer Infantry as a private in Company B. Conn played violin and also enjoyed the very trendy instrument of the day, the cornet. He was soon designated a musician. Conn s unit took part in actions, or was in reserve at Cheat Mountain, Greenbrier, Shiloh, Wartrace, Vervilla and Corinth. Conn left the 15th IVI at the end of 1862. On the 12th of January 1863, he re-enlisted in the First Michigan Sharpshooters Regiment being organized at Camp Chandler outside of Kalamazoo by a Colonel DeLand. His enlistment took place in Niles Michigan, the nearest railway interchange town to Elkhart, with Camp Dearborn as the ultimate designated destination for the unit to train.

However while still at Camp Chandler, Conn behaved with distinction, both positively and negatively, which was recognized accordingly. In February, Conn was promoted to the rank of Sergeant. By the end of the month, he was the first of many trouble-makers hauled in front of a Court Martial. Soldiers from the unit were accused of such as gross outrages upon citizens, particularly female , larceny from dwelling house in daytime , and the more standard drunk and disorderly and absent without leave. Conn, along with Privates Benjamin Waters and Daniel Gore, was charged with maliciously injuring the property of private citizens as well as being AWOL, having returned late from leave. Conn was convicted of only the second charge and the punishment was merely a humiliating dressing down in front of the entire unit. The other two received only reprimands during the hearing, as the example set by Conn was determined by the Court to be primarily responsible for the behavior of his subordinates.

After the regiment relocated to Camp Dearborn, a brass band and music corps were formed to provide a band for entertainment as well as manage buglers. The first commander was Fife-Major Odoniram J. Pettingill of Company D. However, shortly after the formation of the Corps, it lost its key members when D and six other companies were shipped-out to pursue Morgan s Raiders, who had staged in incursion into Indiana. Subsequently, Col. DeLand and another five companies moved to Camp Douglas outside of Chicago in August of 1863 to guard prisoners housed there. The group was reorganized there and newly commissioned Second Lieutenant Charles Conn was detached from his Company G duties and assigned to command the band.

The band practiced 2 hours each morning and 2 hours each evening and performed several times daily as well as for all parade and similar functions. One Confederate prisoner, a German expatriate named Emil Geyer, also joined the music corps as a violinist, performing in officer s quarters. Unusually, the 13 members of the band were excused from all other duties, a practice not normal for military musicians until such was ordered by General Pershing in the summer of 1918, several wars later. Despite this considerable incentive, under Conn s leadership, the band lasted only briefly. By March of 1864, when Colonel DeLand returned after an absence from command, the band seldom performed, with some members out sick persistently, and others simply refusing to play. Upon being informed of the situation, DeLand, together with his Captains, disbanded the band. To continue management of buglers, a new music corps without a band was formed under Drum Major Abner Thurber. Any musician not able to perform those duties was replaced and reassigned to general infantry duties full-time.

Once the unit left Camp in April of 1864, they took part in the battle of the Wilderness and the subsequent actions around the battle of Petersburg. BY June 18th, the unit had sustained such heavy losses to illness, other assignments, injury, fatality and capture, that on the evening of the 18th, only four commissioned officers and 61 men remained available for duty. Lt. Evans was ranking among them and took command of the unit until reassigned several days later, leaving Lt. Conn in charge until the 20th of July, when Capt. Elmer Dicey of Company B returned from a recruiting trip in Michigan. It is unclear if this was subordinate to DeLand, or if the Colonel was absent until sometime before the 30th.

On the 30th, in an attempt to breach Confederate defenses, Union forces dug a tunnel under Confederate battlements and detonated a huge cache of explosives creating a stadium-sized crater. Unwise commanders then ordered Union forces to charge through the crater, the plan having been defined as creating a breach in the lines without regard for the resultant topography. The Confederate forces quickly took control of the high banks of the crater and the result was a disastrous defeat for Union forces, the Michigan Sharpshooters among them. Based on his later complaints of headaches and fainting spells, it appears that Colonel DeLand sustained a closed-head trauma and chronic traumatic brain injury when a shell exploded immediately proximate to him. Conn sustained a flesh wound to the left forearm and was among those captured, including Capt. Dicey and Lt. William Randall.

The officers were taken first to Danville Virginia. In transit at Goldsboro North Carolina, Conn and Lt. Mell of Ravenna Ohio escaped, but were recaptured through the use of bloodhounds. Taken to Columbia South Carolina after Danville, Conn, Dicey and Randall attempted escape there as well without success. They were repatriated at the end of the war. Conn returned to Indiana and mustered-out as a Captain on the 28th of July 1865.

While Conn s service in the military ended in 1865, he joined the Elkhart post of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War veterans association, and was repeatedly elected it s commander. He served as as Lieutenant Colonel of the 2nd Regiment of Uniform Rank of the Knights of Pythias, and first commander of the Knights Templar organization. Most significantly, he organized the 1st Artillery Regiment of the Indiana Legion, serving as its first colonel, and from that time onward being known generally as Colonel Conn .

Conn s second career, that of businessman

Following the war, Conn returned home to Elkhart with an honorable discharge and a love of music. His first venture in business was fairly ambitious, opening a grocery and baked goods store at 22 Jackson Street. He also began selling and servicing sewing machines, all while continuing to play cornet. In these pursuits, he met with modest success. In his spare time, whatever little of that there was, Conn still relaxed like he had as a soldier, indulging in excesses of drink and confrontational behavior.

In 1869, on the tenth of October, C. Girard Conn (as he was apparently spelling his name at the time) married Katherine Mary Hazelton. It appears the couple took up residence in Buchannan Michigan towards 1870, although they are recorded as residing in Elkhart in the census of that same year. The grocery business in Elkhart is referenced both just after the war and as still operating in the 1870s, but in between, Conn is said to have worked for a zinc horse collar-pad company in Buchannan, where he learned the machining skills for his next step in business. While on the job there, and moonlighting as local band leader, Conn is said to have seriously hurt his hand, ending his ability to play violin.

It is in Buchannan that one of at least two viable stories regarding the invention of Conn s first product, the padded rim mouthpiece, takes place. While Conn is not mentioned in any source of the period, many years later it was conjectured that he is one of the two ethnically Irish non-locals referenced in an incident where they purportedly chased-down and cornered a local African-American youth. The youth then ended the assault by dropping the lead pursuer with a single punch to the mouth. This took place around July of 1872. Conn and his wife moved home to Elkhart, which was about 25 minutes by rail through Niles and Granger, soon thereafter.

The second story is more simple, and was likewise first described long after the event. That is that Conn and Del Crampton were drinking in a bar and got into a fight which Crampton won. In either case, Conn s lip was damaged and cornet playing became painful as he recorded in an edition of Trumpet Notes in 1881.

Working out of his store, Conn engaged in several businesses including the sewing machine business with Jake Misch, engraving and replating silverware (one ponders the prospect of silverplating baths adjacent to food handling), producing and selling a snake-oil type curative, and the manufacture and sale of rubber stamps with John Rodgers.

In late 1874, Conn hit upon an idea to put the rubber stamp material on the flat rim of a cornet mouthpiece to cushion it. The padding worked, but would not bond firmly to the flat brass surface of the mouthpiece. He then took a derelict sewing machine, and converted it into a form of lathe, which he used to cut a groove in the mouthpiece face. Patenting the idea, Conn began remanufacturing other s mouthpieces for sale as his patented cushion rim piece.

In 1875, Conn moved the new business to the top floor of the McGregger & Sons Woolen Mill and by the end of the year had established a brass foundry next door to produce mouthpieces of his own.

The following year, Conn recruited a former employee of the Henry Distin firm in England, Eugene Victor Jean Baptiste Dupont (1832-1881)to form a partnership with him called Conn & Dupont. Distin sold out to Boosey & Co. around this time, which may have been a very fortuitous coincidence motivating Dupont and making possible Conn s education in the business of band instrument manufacture.

The partnership ended in March of 1879, and the company became simply C.G. Conn. Among the early products of the company were some cornets closely modelled on Distin products, and one that was unique. The Conn 4-in-1 cornet, likely designed by Dupont but starting a corporate obsession with innovative cornet design that would last until the Great Depression, sold well enough to establish the company as a major competitor in the field.

While this would begin Conn s transition to his third great career as an instrument maker, Conn s other two interests would not be abandoned. As an additional business venture, in 1889, Conn founded the Elkhart Truth newspaper, which continues today as a web publication. He also bought the Washington Times in 1895. Becoming a champion of bringing the truth to the people, it was only logical that he would exploit the opportunity to shape the story, and ran successfully for public office, serving in the Indiana legislature 1889-1892, and the Congress 1893-1897. He had previously been elected Mayor of Elkhart in 1880 and 1882. He declined to run for another term in Congress in 1897, in order to combine his interest in the retail sector with the booming instrument business, and opened a retail store in New York City that lasted until 1902.

In 1908 Conn lost a bid to become Governor of Indiana, and also failed in an attempt to run for the US Senate in 1910. His publications, The Elkhart Truth, The Washington Times, Trumpet Tunes, and the CG Conn catalogs demonstrated that media was not just a business venture for Conn, nor a means to the end of getting elected. Conn, it seems, had a deep interest in the media, and in having his voice heard.

One of Conn s failures in his diverse business endeavors came when he attempted to build an electric utility in competition with the local, established generating firm in 1904.

As a wealthy businessman, Conn was able to buy the most ostentatious home in Elkhart, the 1884 Strong Mansion at 723 Strong Ave., to add to his public image of achievement in business. He purchased to home in 1890 and hired architect A.H. Ellwood to drastically expand it including the portico, which was claimed to cost $10,000 in an Elkhart Truth story.

Conn s third career, Instrument Maker.

With the knowledge gained from the Dupont partnership and the revenue stream from growing sales, Conn was able to expand the company and build a nationwide distribution network. On Conn s birthday in 1883, the mill buildings burned, but Conn immediately rebuilt. The success of the business was sufficient to secure the necessary financing, and the new factory would grow continuously from the initial reconstruction until it too was destroyed in 1910.

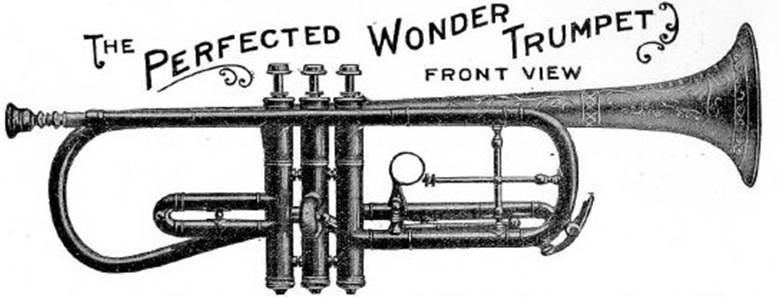

The Conn Company produced many innovative products around the turn of the century. These included the Conn Wonder cornets, first produced in 1883, such as the solo model depicted below and the vocal version below that both loosely based on the Courtois Arbuckle wrap.

The Conn trumpets began as a lesser interest for the company. The first appear to be very similar to cornets, although some are quite bizarre.

A later Conn advertisement read in part If you want a real Trumpet, an Instrument that is the real thing with a cutting, piercing, strident tone, buy the C.G. Conn Symphony Trumpet. That is what all the great trumpet players do. The apparent bias against trumpets might be a result of Conn being a cornetist and feeling, as Clarke voiced, that such harsh language correctly describes the instrument though that is pure speculation.

Conn expanded further in December of 1886 buying the Isaac Fiske Instrument Works in Worchester Massachusetts. The factory continued to produce some of the same instruments but over time transitioned to building Conn designs. This venture was shut-down at the same time that the New York retail operation was launched in 1898.

One of the unique innovations of the turn of the century company was the Sousaphone. Based on the common helicon version of a tuba, the first Sousaphone was created by James Welsh Pepper in 1893 at the request of the legendary band leader. However, Conn s marketing machine recruited Sousa and his band to the Conn stable early on and with Conn s ability to mass-produce such instruments, Conn became seen as the originator of the instrument. Without Conn, certainly the instrument would likely have vanished without much notice.

Of course, Conn s most interesting, and absurd, variant of this concept was the rain-catcher Sousaphone, which turned the bell upright. As the purpose of a helicon or Sousaphone wrap is to orient the bell in a manner that the sound will project where the ensemble needs it, this means of replicating the very difficulty with regular tubas that the instrument was created to address, seems quite odd.

In 1893, Colonel Conn s net worth was estimated in excess of a quarter million dollars.

The Fire and Colonel Conn s Retirement

Disaster struck the Conn Company on the 22nd of May, 1910. While Colonel Conn and his wife were on one of their frequent trips to California, the wood framed and interior plant, which by that time covered an entire city block several stories high, was razed to the ground by fire. The facility, tools and inventory lost were estimated to be in excess of a half million dollars. Fear took hold in Elkhart, fear which would later be borne-out by events, that the Colonel could not sustain such a loss and that the largest employer in Elkhart would vanish.

The residents of Elkhart organized to meet the Conns who rushed back from California, with large numbers gathering on the platform. The Conns then joined in a parade, along with the public safety responders who had fought the blaze.

In April of 1911, in Mrs. Conn s name, a trust deed to facilitate the ten-year bonding of working capital to rebuild as well as retire existing debt, was written against all of Conn s property including the former plant, the Elkhart Truth, a scale company, the Conn farm (where the new plant was to be built at what today is 1101 Beardsley), the Conn mansion (originally the Strong mansion), a yacht, another boat, shares of stock and several other real-estate holdings, totaling roughly $200,000.

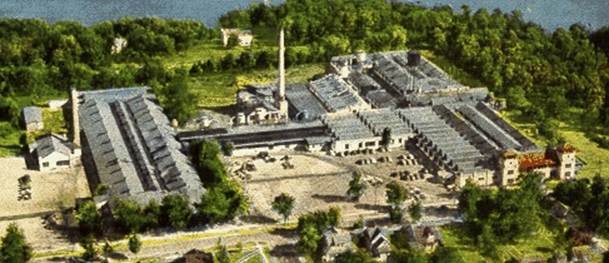

In December of 1911, the smaller replacement plant was ready to open as shown in a Conn postcard.

Like its predecessor, this plant would grow continuously, but without Colonel Conn directing that growth. By 1915, Conn s financial problems had not lessened and Conn sold the company along with much of the property backing the bonds, to an Ohio millner named Carl Diamond Greenleaf. Greenleaf admitted that, other than being a mediocre alto horn player, he knew nothing of the business. At the same time, the longtime plant manager, William Gronert, who had worked at Conn through both fires, left. Greenleaf and his fellow investors were starting over in a new facility without the commanding officer who had built the company.

Conn had come from modest beginnings, and through the adventures of his youth and earlier careers had ample ability to exist at any level of wealth or poverty. For most of their married life however, Mrs. Conn and their relationship had known a brief period of middle class existence followed by the luxury and convenience of being business owners at the end of the gilded age.

This was a time when the wealthy were mindful of their obligation, or so it was perceived, to be employers, and typically employed large numbers of servants. While Colonel Conn could undoubtedly have walked to the kitchen (and if necessary pumped) to get a glass of water, it was expected to ring for a servant to do this. While normal folks carried cash, or when making large purchases cumbersome check ledgers and proofs of credit, the Conns only had to walk into a business and they would be recognized. Service would be provided, goods would be sent to the house, the invoice would be sent later and paid by Conn s employee for such matters, and the Conns themselves were never bothered by the price or the process.

This, of course, came to an abrupt end in 1915.

Mrs. Conn did not adapt to the new reality, and the Conns divorced. She shared the mansion in Elkhart with their daughter, and Colonel Conn relocated to California where he lived a more modest existence in retirement, taking a new bride much younger than himself, Suzanne Cohn. They had a son, C.G. Conn III, together in 1918. Col. Conn returned to Elkhart just once in 1926, two years after his first wife s death, staying with his surviving sister.

Colonel Conn died in Los Angeles on the 5th of January 1931, having lived to see a time of great national trauma and not only financial, but life and death struggle evolve to a time of economic prosperity, another time of terrible conflict with World War One, and then following the boom of the 1920s, the devastation of the Great Depression. When Conn died, he was among the few Americans who had the experience to know that despite the great hardship, recovery would come. For him however, it would not, and when he died, his funeral and burial at Elkhart s Gracelawn Cemetery had to be funded by the passing of a hat at the Conn factory, which by then was the largest the company had yet known.

The Greenleaf Era

Carl Greenleaf, along with his chosen successors Paul Gazlay and Carl s son Leland Greenleaf, accomplished tremendous transformation and growth. The company was reincorporated as CG Conn Ltd.

The first great change instituted by Greenleaf was to organize the product. Instead of ephemeral names, each instrument would be designated by type and model. For the types, and alphabetic character was assigned. Cornets having been the first product, were designated A . Trumpets were designated B , trombones D , euphoniums I and a host of other letters, each assigned to an instrument type. Then, each model received a model number. Where there were instruments such as trumpets that could either be ordered as a simple low pitch B-flat instrument, or with all the options (and spare parts) of both high and low pitch with change by slide or rotary valve slide to the key of A, the two kits were designated by consecutive numbers such as the basic 4B and its companion the 5B. This made identifying models and options much easier not only for production tracking, but also for the customers and retailers.

The Elkhart Truth was sold to Andrew Hubble Beardsley and Carl Greenleaf. They also partnered in the Elkhart Band Instrument Company, which Beardsley subsequently sold his Buescher Band Instrument Company, originally founded by the fifth employee at Conn & Dupont, Gus Buescher, to.

The naming convention for instruments was fully implemented by 1920, and included designations for saxophones. Buescher had seen success with the instrument, and this was likely communicated to Greenleaf by Beardsley. In the early 1920s, the Conn company produced a full line of saxophones and patented several innovations. The company had sold imported saxophones as early as 1881. Starting in 1922, when saxophone production was already at some 150 units per day, Conn offered an option that would not become popular for almost a century colored lacquer not just in the amber and gold used by other firms, but in pastel colors.

Another early action taken by Carl Greenleaf that seems to suggest a lesson learned from Beardsley was to launch a separate wholly owned subsidiary to sell to the student market. The Pan-American brand initially benefitted from hand-me-down obsolete Conn designs, and subsequently also developed unique low-cost designs of its own. Pan-Americans were sold extensively into the stencil market, with retailers able to order trim variations to identify their brand uniquely from other Pan-American stencils.

Greenleaf further developed this channel by aligning with leaders of the emerging school music movement such as Interlochen founder Joe Maddy, to whom Conn contributed $10,000 toward the establishment of the National Music Camp. Greenleaf also sponsored the first national band contest in Chicago in 1923. With the establishment of Conn s experimental laboratory in 1928, the Greenleaf team developed not only leading-edge break-throughs in instrument design, but the StroboConn Tuner (1936) that became a fixture in school music rooms nationwide.

The 1920s became a period of great growth at Conn and with the revenues poured back into research and development, Conn began producing some of the best instruments available. This solid footing allowed Conn to weather the Great Depression, although a complete change-out of the model line-up did occur in the course of seeking more cost-effective manufacturing of a streamlined portfolio. Conn purchased Haddorff Piano in 1940 and began production of Conn Pianos.

The Second World War

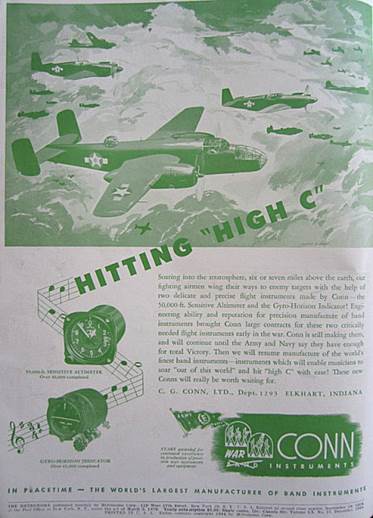

Unlike World War One, when General Pershing s restructuring of military music, replacing adhoc ensembles with professional musicians and expanding both in number and instrumentation, had resulted in a boom of orders for instruments such as the trumpet below, in 1942, the Defense Plant Corporation, which semi-nationalized all manufacturing capacity, repurposed Conn to make precision instruments such as altimeters and compasses.

Conn produced advertising during and after its period of nationalization that details what the company was doing during the period.

A Conn Altimeter is pictured below.

Post-War

As shown on the postcard below, the factory during the Second World War was very large. And, as Margaret Banks points out with regard to this image in her Conn history, surrounded by a very substantial fence for security during the war.

Paul Gazlay replaced Carl Greenleaf, though the family retained ownership of the company, in 1949. He proceeded to absorb or sell all of the subsidiaries Greenleaf had accumulated including Pan-American, Elkhart Band Instrument, Ludwig & Ludwig, Leedy, and Haddorff Piano. Conn also owned half of the H&A Selmer Company of New York prior to the war, and continued this holding.

After the war, The experimental laboratory grew into the Division of Research, Development and Design headed by Dr. Earle Kent. Among its successes were the more portable StroboTuner, the first all-electronic organ named the Connsonata, the electronic Clinician (a combination tuner/spectral analyzer), the DynaLevel (a visual audio-intensity monitor), and among instruments, the fiberglass Sousaphone and the Constellation line of brass instruments.

In 1958, Leland B. Greenleaf assumed the presidency after 30 years with the firm.

Initially, Leland continued the expansion that had characterized the Conn Company since 1876. Firms acquired included Janssen Pianos, Artley Flutes, and the Scherl & Roth company which produced strings and for a time the Roth stenciled line of Reynolds brass. New factories were built in Arizona for Pan-American, in Madison Indiana for the organ division, and a new plant in Elkhart that would one day become the home of Bach Trumpets.

In 1963, serial number 1,000,000 was celebrated, although since Pan-Americans used a separate sequence and some instruments such as bugles and drums were not numbered, it was well beyond the one millionth instrument built.

By the end of Leland s tenure however, the market had changed. Band instrument sales were stable, but new manufacturing techniques allowed firms to market cheap lower quality instruments in huge numbers. As everyone over-produced the market, Asian firms began to explore the market as well with higher quality at the same low price. Conn s stock began to decline sharply in the later 1960s. Leland opened negotiations with Collier-MacMillin publishing, and also had the foresight to donate the entire Conn instrument collection to Interlochen, where a 900 foot long building, essentially a hallway lined with display cases, was built to house it.

The company that had been CG Conn essentially ended at this time.

Transition to conglomerate

During the 1970s, MacMillin disposed of the company records, including designs, and closed down many facilities, relocating to low-cost regions to manufacture. Conn left Elkhart entirely at this time. While costs were lowered, the quality was perceived to have changed likewise. Sales of all Conn brands continued to fall short of expectations. The third plant was sold, and ultimately demolished.

In 1980, a former Conn employee named Dan Henkin who had left in 1970 to buy and run Gemeinhart Flutes, and who had sold the company to CBS in 1977, purchased Conn from MacMillin. His stated intention was to return Conn to Elkhart, but that did not happen. His brief tenure did see the acquisition of W.T. Armstrong, the purchase of King Musical Instruments and the launch of the successful Severinsen model trumpet, but in 1985, Henkin sold all but the Slingerland Drum division to a Swedish investment firm.

The holdings, renamed United Musical Instruments, were resold immediately to an investment group headed by Bernhard Muskantor. UMI shut-down some of the brands, but also acted to move woodwind production from locations such as Mexico to the former Armstrong facility in Elkhart. Many brasswinds were consolidated at the King plant in Eastlake Ohio, where they remain today.

In 2000, UMI was purchased by Steinway & Sons and formed into the Conn-Selmer Division of Steinway Musical Properties, which subsequently became Steinway Musical Instruments. Merging into the Conn-Selmer Division over the following seven years were the Leblanc companies including Martin and Holton and the rest of Selmer. Following a take-over attempt by the Korean firm Samick Musical Instruments, which specializes in relocating high-end piano manufactures to Asia and employing new low cost, high-speed manufacturing techniques and materials, Steinway was taken private in 2014.

At present, the Conn name appears on instruments made primarily in Eastlake Ohio, and on stencils of Prelude and similar Asian made instruments.

The only portion of the Beardsley Ave. plant not demolished, the newer part of the North-West corner, sits drastically remodeled and abandoned today, with the sidewalk in front as a reminder of its once grand Mediterranean-style appearance.