A Glimpse through Brass

into the beginnings of the King Musical

Instrument Company

A historical

Hypothesis

Drawing on the evidence of the instruments themselves

by Ron

Berndt

August, 2012 – Amended October 2015

As so often happens, those who build great enterprises or

who shape the future rarely take time from their considerable endeavors to

clearly record how they achieved what they did. King Musical Instruments is a

shell today of the great twentieth century American instrument maker that it

was, but the activities of H.N. White & Co., the company that eventually

adopted its longtime tradename

“King”, significantly helped shape the evolution of band instruments and the

school music movement. There are a handful of rare instruments that survive

from before H.N. White had the resources to manufacture more than a few

hand-built trombones, and they give us a sense and vision of the earliest days

of the company. Recently, a restored cornet of a previously unseen-in-modern-times

attribution has surfaced and may be the oldest surviving cornet sold by Mr.

White in his fledgling business. Once understood in context, it and other

survivors allow a reconstruction of the probable activities of the early firm,

and shed light on how that time differed less than we might think from our own.

Henderson White was born in the then less than a century old

farm town of Romeo Michigan on July 16th 1873 to carpenter and

builder George M. White and his wife Eliza. Born there, George would spend his

entire short life from 1839 to 1879 in the small town. With his father having

died when Henderson was only 6, by age 12 he had to leave school and apprentice

to a builder named Galloway as a carpenter. At age 14, apparently finding his

father’s trade not his direction in life, Henderson White took up employment in

the Detroit music store of Mr. O.F. Berden where he

discovered his talent for instrument repair and engraving. By age 16, what must

have been a natural talent for the trade had already made his name known in the

business and he was recruited to leave Detroit for Cleveland Ohio.

Both the 1910 biography of White in Samuel P. Orth’s History of Cleveland and great-grandson Chris Charvat’s biography on the website www.hnwhite.com, speak to

White working for McMillin’s music store for 5 years.

When White moved to Cleveland at age 16, the year would have been at least late

1889. However, in 1889, George McMillin was still

employed in the music publishing house of J.G. Richards & Co.. According to the Presto trade publication’s December

1924 obituary for McMillin, who died of a stroke at

his desk at work, McMillin “parted ways” with

Richards and started his firm in 1892. Charvat records that White briefly partnered in the firm Berg & White

before becoming sole owner of the company in 1893. At best that leaves 5

calendar years between his arrival and the partnership, but only 2 during which

McMillin’s store was in business. It can only be

guessed that perhaps he worked with McMillin at J.G.

Richards, or that perhaps McMillin opened his store

before leaving Richards.

Regardless of his employer during his first years, in 1893

Henderson White partnered with C.H. Berg, whose sister Elizabeth became his

wife on September 20th 1894. By that time the partnership was over

and H.N. White had opened a small music store on Woodland Avenue. It is this point in the history of King

Musical Instruments into which the recently rediscovered cornet gives us a new

perspective.

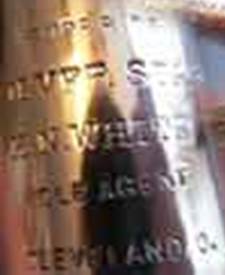

At the website www.horn-u-copia.net one can find

several similarly inscribed cornets indicating that they were sold by a “sole

agent” for Cleveland. Some of these are engraved with McMillin’s

name and some with White’s. Horns made by one firm labeled for sale by another

are known as “stencil” horns. Previously

known White stencils are labeled with the name “Silver Star”, “Union” or

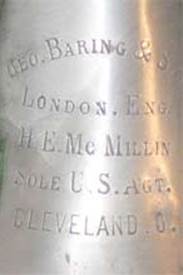

“Imperial”. The McMillin horns are engraved with an

attribution to “Geo. Baring & Co. London Eng.” – though no other trace of

that firm seems to exist. In both cases, the bell engraving is usually simple

text. Common distinct elements appear across names and models, but occasionally

elements also are distinct by agent name on otherwise same models. (photos from www.horn-u-copia.net)

The newly rediscovered cornet is a near-perfect copy of a

lesser known Besson short cornet. When comparing, one

must compensate for minor visual differences that result from the largely

manual process of bending and forming brass instruments in the 19th

century, but the commonality of parts and general form can be seen upon close

inspection. The only obvious non-Besson attribute of

the horn is that the tuning slide brace has no diamond-shaped escutcheons at

the ends. When comparing to the 1896 version of the Besson

original, it can be seen that the Besson ferrules

used at the valve slide radius unions are more elaborate than on this horn or a

matching McMillin stencil attributed to Baring &

Co. However, Besson

restructured in 1894 with a public stock offering and began a series of changes

to design elements over the following years. By 1900, not only had these

ferrules changed, but the tuning slide brace became a wire loop, the all metal

thin finger buttons became taller pearl-topped ones and the valve caps onto

which they descended changed to use felts, eliminating the problematic cork

risers.

An 1896 Besson (horn-u-copia.net)

A McMillin by Baring (horn-u-copia)

& the subject White by

Bauer

The engraving on the White stencil cornet attributed to M.

Bauer reads:

SUPERIOR

M. BAUER & CO.

H.N. WHITE

SOLE AGENT

CLEVELAND O.

The typeface, format, placement and so on are completely

consistent with the Silver Star / White cornets that are well documented. The

tooling is more significantly a match for the markings on McMillin

horns believed to have been marked by White himself. The

questions of who made the instrument, required considerable deduction and

testing of hypothesis.

It is best to work through the attributions on the bell line

by line. The first, “Superior”, appears inconsistently on instruments that list

H.N. White as “sole agent”. Some have treated Superior Silver Star and Silver

Star as separate trade names. The identical usage of the word on this

instrument, along with the difference in typeface from the next line in either

case, suggest strongly that superior is not a part of the tradename,

but rather is a quality declaration. Many British instruments of the time, as

well as others, would have “Class A” or “Class B” and so on denoting the

quality of the particular model as the first line of the bell engraving. The first

logical deduction regarding this horn then is that young Henderson White

observed this in the instruments he sold at his earlier music store jobs and

decided to copy it - but with his own, more American sounding classification.

To derive a sound supposition similarly with regard to the

second line is a more complex question. To consider fully if “M Bauer &

Co.” is a made-up entity, one must consider the other contrived brands and tradenames of the time as well as the possibility of a real

firm.

McMillin, where White worked

immediately prior to starting a business in which he too would sell stencils,

sold stencil horns attributed to the firm of George Baring & Co in London.

There seems to be no record of George Baring and his firm in England at the time.

A George Baring had founded Barings & Co. in London in 1802 to engage in

far-east trade, and Baring Brothers & Co. (Barings Bank) was the world’s

best known mercantile bank, but no record seems to remain of a firm in London

by the name of George Baring that made instruments. The notability of the

Baring name, being an old, globally known family of politicians and bankers,

would undoubtedly have seemed familiar and prestigious to potential customers.

Based on the lack of evidence of Geo. Baring & Co., as well as the

generally pricey nature of British and French instruments of the time, a second

deduction may then be that McMillin created the name

of a fictitious London firm to enhance the image of a supplier-built generic

cornet.

Likewise, the Bauer name was known in the Midwestern United

States in the 1890s through the Julius Bauer Piano Company that sold stencil

horns in his “J. Bauer” name that were made by his Bohemian cousins,

principally Eduard Johann and Johann Adam Bauer in the 1860s and 1870s. By the

early 1890s, one notable cousin was still producing these instruments, that

being Albin Bauer. Matthaus

Bauer built a variety of instruments including brass in Vienna starting before

1838, but his details of construction including ornamentation, elaborate

marking, bracing, and traditional rotary valve imperial wraps differ vastly

from this horn. Starting before 1838, it is doubtful he still would have been

building at all in 1894. There do not appear to be any “M. Bauer” signed brass

instruments from 1890s Europe. A New

York Times notice of probate indicates that Julius Bauer died in 1884 leaving

his wife Anna Marie and her brother Andrew Mueller in charge of the estate.

Later, his son William would head the firm but Julius’ name was retained on the

instruments until the firm was taken over by Wurlitzer during the great

depression. Known brass instruments by various Bauers

include rotary and berliner

valves, but no perinet valve horns. Given that the

only Bauer who’s name started with M would have been

quite old in the 1890s and never built anything similar, this seems well able

to have been another example of playing on a familiar sounding name. The third

deduction thus is that the name M. Bauer on this horn is a case of H.N. White

following the example of his recent mentor, not just in supplier choice, but in

fabricating a familiar sounding European maker to add prestige to his

supplier-built instrument.

While building this chain of supposition,

the next logical answer that can be deduced regards the point in the H.N. White

corporate history where this instrument best fits. As noted above, the

ferrules indicate that this is a copy of a pre-1896, possibly pre-1894

restructuring, Besson. White sold stencil cornets in

the 1890s and even into the 1900s using tradenames

rather than those of a purported maker. As he continued to use tradenames on lines of instruments of his own making, the

flagship of which was King, but which included examples such as Liberty, Silvertone, Silversonic and

Silver Flair, through the end of his life, it stands to reason that the

differing practice of naming a maker must pre-date that of using a tradename. Logically then, the fourth deduction must be

that this “M. Bauer” horn predates his other stencil products and may

reasonably date from 1894 give or take a year.

The remaining three lines are consistent with all of the

stencil horns sold by the H.N. White Company that exist and demonstrate almost

conclusively that this is one of those horns. The leather satchel case

accompanying the cornet also is of the dark textured leather common at the turn

of the twentieth century and appropriately aged. While it is not impossible, it

is extremely improbable that this instrument could be an expensive and

incredibly complex hoax targeting King aficionados.

Taking into account that , as will be explained later,

the number on the second valve casing, which is 7, is a model, not a serial

number, the fifth, and most significant,

deduction regarding this horn is that this is among the first cornets, and for

that matter instruments, ever sold by Henderson N. White in his own business.

Where the instrument was manufactured was a question that

required access to more examples to resolve.

As shown above, there are identical horns as both White & McMillin stencils. This suggests strongly that they shared

one or more suppliers of these instruments. There are those including the

authorities at www.horn-u-copia.net who treat George Baring & Co. as a real

company attributing White & McMillin stencil

cornets to it - though as already noted, that is unlikely. Likewise, Matthaus Bauer existed near the time in question, but is

equally improbable as the maker. Fabrication of the McMillin

and White stencils has also been attributed to Alexandre Le Forestier,

who apprenticed at Besson, worked for Curtois and Distin, and was a

foreman at Pepper before setting up an instrument making shop in Philadelphia.

Given the intense similarity to established makers’ cornets built near that

time, speculation that they are factory seconds, or absconded parts and designs

straight from the design originator’s plants, is always a plausible theory in

such cases.

One possible source considered for these horns is the

Standard Band Instrument Company of Boston. In 1862 David Hall founded the firm

at 62 Sudbury Street across from the successful E.G. Wright factory that also

housed Graves & Sons – who combined in 1869 to become Boston Musical

Instrument Manufactory. Hall struggled and took on new partners reincorporating

in 1870, and 1871. In 1876, his partners bought him out and formed Quinby brothers, which in turn failed and was purchased by

the struggling publishing house of Thompson & Odell in an attempt to

diversify in 1889. Thompson & Odell Publishing fared poorly and was

absorbed by Carl Fischer in 1901. By 1905 what had been named the Standard Band

Instrument Company was bankrupt and negotiating to be purchased by Vega Banjo –

as happened in 1909. Sometime during the transition to Vega, a cornet closely

matching the Bauer/White and Baring/McMillin was

produced under the “Vega made by the Standard Band Instrument Company” label

and listing the old DC Hall address. Failing companies routinely stretch the

life cycle of old product and by the time Vega was involved with Standard, this

model would be dated. Likewise it is reasonable to suppose that a struggling

firm, which Standard was historically, particularly during the economic

upheaval of the 1890s, would have been willing to sell product for others to

stencil under their own names. Rationally, the bankrupt Standard could have

been sourcing this horn outside themselves to reduce

labor costs, it would have been poor strategy to choose such an outdated model.

As it turns out, they, like McMillin and White, were

sourcing this generic product from a low-cost supplier and branding it for

their use.

(1905-9 Vega/Standard

photo from www.horn-u-copia.net above with the 1890s White/Bauer)

Ultimately, with access to the extensive photographic

holdings of Kenton Scott and the horn-u-copia

website, several of this series of models (at least 11, each denoted by a

similar model number on the second valve casing), were identified. Many trim

parts change, and they exist as many different wraps, but the set includes the

Marceau cornets sold by Sears and others known to be products of Bohland & Fuchs in Bohemia. Some of the set bore

markings indicating B+F manufacture.

White would continue to buy horns from B&F such as the

Union cornet below left, and for many years after this line was discontinued

around 1900, such as the second generation Silver Star model below.

This, then, is our first glimpse into the early days of the

H.N. White Company: As Henderson White, then only 20 and getting married,

ventured out on his own in business, he must have split his time between

business requirements such as stocking and the books, and his workbench where,

when not repairing customer instruments, he could produce a very few “King”

trombones - tradenamed after Thomas King, who had

helped him perfect his design. Perhaps it is White himself, noted as an

engraver amongst other skills, who stenciled these first cornets upon their

arrival at his bench.

By the turn of the century, White was ready to expand and

produce his own cornets with the King Famous Short (1906 pictured above), King

Large Bore, King Small Bore, and King Long Model cornets. In the first decade

of the century, Conn, Holton, York, Lyon & Healy and others all were

experimenting with new designs for larger, heavier and more conical cornets. In

designing his first horns, H.N. White elected to expand upon the old-looking,

but proven, wrap he knew from Besson and Conn. White

and McMillin had stenciled horns similar to the C.G.

Con Wonder design as well as Besson horns, and Conn

in the 1890s was marketing this exact wrap in one of their other cornets.

History ultimately vindicated this choice of design, as that simple wrap

out-lived all of the wild contemporary creations of the early twentieth

century, becoming the standard form of the modern cornet. Pictured below are the original 1860s Besson wrap and the Conn version circa 1897 (from www.horn-u-copia.net).

Continuing the early story of HN White, in 1906 he finally

moved from the small shop into a production facility at 1870 East Ninth Street,

before which his capacity must have been severely limited. His stencil cornets

have by many been believed to date from the time between the establishment of

his first store and his entry into cornet manufacturing around 1900. However, a

White stencil “Imperial” appears to be based on a C.G. Conn Perfected Wonder,

which debuted in 1906. This stencil, called an American Model Cornet by its

manufacturer Bohland & Fuchs, is pictured below.

The New Invention Circus Bore Cornet replaced the nearly

identical Perfected Wonder model in 1910. By this time, White had been building

King cornets for over a decade. Sometime after this,

but before 1920, White began building the Imperial himself, but marking it as a

stencil. It interestingly shares a distinct detail with McMillin’s

Crown brand cornets circa 1905, which is a knurled rope accent on the union

ferrules. White was supplying these to his former employer while also selling

them himself. Thus one may plausibly deduce that White continued selling

stencils alongside his own cornets in order to give his rapidly expanding

distribution network more variety than he had the capacity to make -perhaps

until the larger factory at 5225 Superior Avenue was fully operational after

1911.

McMillin Ferrules C.G. Conn New Invention Circus Bore

(horn-u-copia)

Imperial, HN White Sole Agent, Cleveland O.

The Imperial was ultimately renamed the King Junior in 1920,

and the Crown Brand ferrule disappeared in favor of standard King ferrules

after McMillin’s death at his desk in 1924.

When the Depression struck, White shut down the recently

purchased Cleveland Band Instruments and temporarily returned to stencil sales,

placing Cleveland and their other bard American Standard on supplier-built

horns. At the same time, White leveraged that supplier relationship to build a

student pea-shooter trumpet, the Student Prince, which is shown below. White

stencils finally ended before 1940.

So, through supposition based on what record remains and

surviving instruments, the world of young Henderson White in the first decade

of what would grow rapidly into one of the world’s leading and most innovative

band instrument companies comes into view – if only a little bit. He maximized

his own skills and meager capital, using techniques not unlike those used by

instrument retailers still today, to provide the

widest selection at the lowest price he could, in order to facilitate that

growth and ultimate achievement. It was the stencil horns, the equivalent of

our Chinese-produced horns with familiar old names, as well as

name-of-the-month horns through online retailers, which ultimately built the

customer base and funded the expansion into a full manufacturing concern -

which then grew into the band instrument powerhouse that lasted most of the

twentieth century. The young Mr. White could have been born over a century

later, followed the same life plan, and prospered to the same degree as he did

- as the business model has not changed nearly as much as we might wish to

believe.

Sources:

Ø

Orth, Samuel Peter, A

History of Cleveland Ohio Illustrated, SJ Clarke Publishing , Cleveland Ohio,

1910 , P. 1092

Ø

Charvat, Chris, The

Henderson N. White Story, at http://www.hnwhite.com/hnwhitepage.htm

Ø

Staff, Julius Bauer’s Estate, The New York

Times, NY, NY, December 30, 1884

Ø

Staff, Cleveland’s Pioneer Music Man Dies,

Presto, December, 1924 at http:// presto.arcade-museum.com/PRESTO-1924-2004/PRESTO-1924-2004-09.pdf

Ø

McMillin, H.E.,

Catalog of the Crown Model Band Instruments, Cleveland, Ohio, 1904

Ø

Database of instruments at

http:www.horn-u-copia.net

Ø

List of Besson Serial

Numbers at http:www.horn-u-copia.net

Ø

List of King Musical Instruments Serial Numbers

at http:www.hnwhite.com

Ø

Myers, Arnold and Eldredge,

Niles, The Brasswind Production of Marthe Besson’s London Factory, Galpin Society Journal, volume LIX, pp43-75