A History of Frank Holton & Company

Ron Berndt, 2015

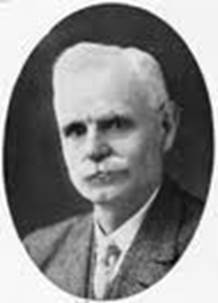

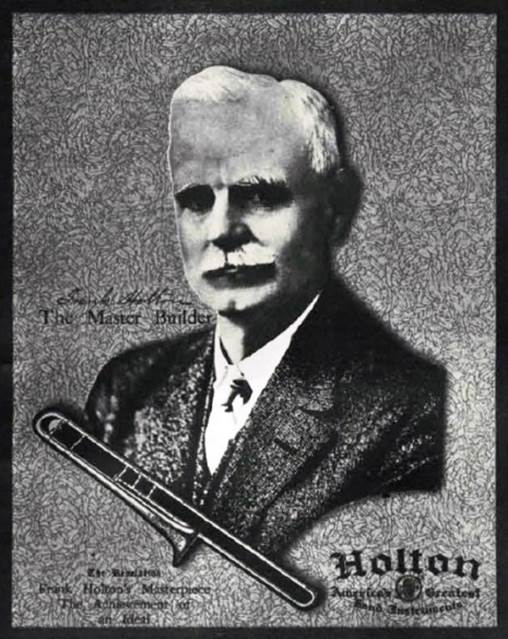

Frank Holton was born September 28 1857 to a farm family in Allegan County Michigan. His Mother, Mary Clark Holton, played organ and his father, Otis L. Holton, was in the choir of the church the family attended. He started on cornet before taking up the trombone. His professional playing experience ranged from circus bands to ultimately being part of the famed Sousa Band under Marine bandmaster and composer John Phillip Sousa along with such low-brass notables as Simone Mantia and Arthur Pryor.

Holton first ventured into business in 1885, partnering with James Warren York for a year. York had apprenticed in the James Keat tradition at the Boston Musical Instrument Manufactory firm under Henry Esbach and Louis Hartman. The exact nature of the York partnership is unclear, but it was a corollary to York’s Band Instrument Manufacturing firm in Grand Rapids that would go on to make some of the most renowned low brass instruments of the early Twentieth century. This venture appears to have been primarily an investment, and Holton did not alter his primary employment as a professional trombone player - though it may have been related to no longer working a full time job otherwise as well.

Holton recalled for an interviewer that it was around 1896, when he was playing in Ellis Brooks Second Regimental Band in Chicago that he began a mail order enterprise selling his own unique formulation of trombone slide oil developed in 1895. As of 1898, the business was still in the red. Not willing to give in to what he felt was the popular view that musicians could not succeed in business, and feeling that at age 42 he had peaked in his playing career after far exceeding his dreams in that field, he determined to expand rather than give up. Holton rented a second floor retail space on the Northeast corner of Clarke and Madison streets in Chicago. Starting with a simple counter, $5.00 desk and chairs, he began to sell not just supplies such as his slide oil, but used band instruments.

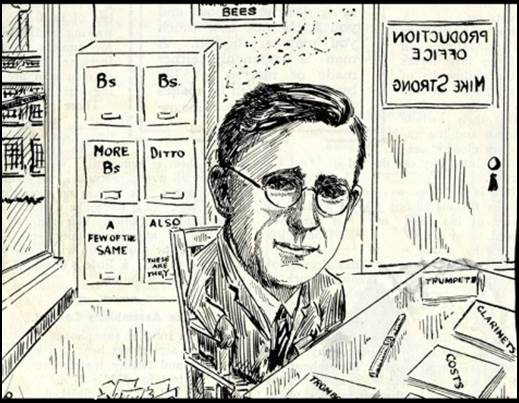

The start was a slow one and Holton continued playing to pay the bills, but gradually the business took hold. Holton was no stranger to working a full time job and playing professionally. He had been a blacksmith building carriages for Cahill & House in Kalamazoo in the 1880s when his career began. His wife, Florence, taught music to help cover the cost of their $10.00/month flat. By November 1900, Holton employed an office boy, Mike Strong (then age 14), three instrument makers/repairmen, and a stenographer in a two room suite at State and Madison, the revenues having financed a larger space that year. Starting at $0.25 an hour, Strong remained with Holton becoming purchasing agent, and then head of bell making and bending. In 1929, he was profiled in the company newsletter.

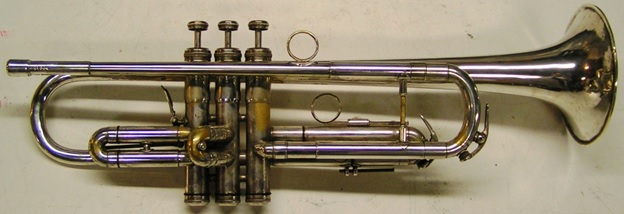

During the first years in the store, a small number of instruments were assembled by the repair staff. Chief among these were cornets built in the 19th century short cornet style and using pitching shanks. Many of the parts were likely purchased from generic suppliers, but the core fabrication was done on the repair bench. At left, with the low pitch tuning slide installed and the high pitch slide in the foreground is cornet #318 made around 1901. The “Old model, as it was later called, remained in production into 1907.

Holton recalled that it was one of these early summers that a man named George Renner walked into his then third floor store looking for a particular instrument. The Holton and Renner families struck up a strong friendship that was what first prompted Holton to visit Elkhorn Wisconsin, where the Renners lived. Holton’s decision to build his final factory there began with that chance encounter. But first came the Chicago plant.

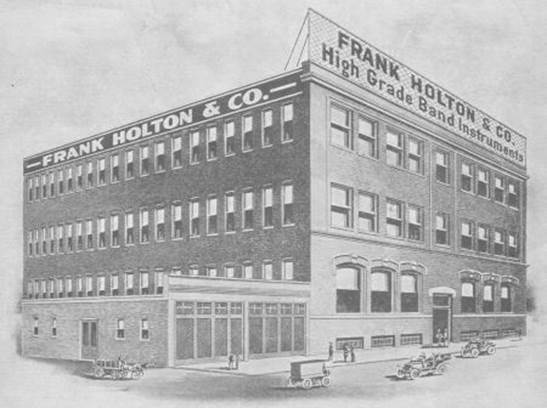

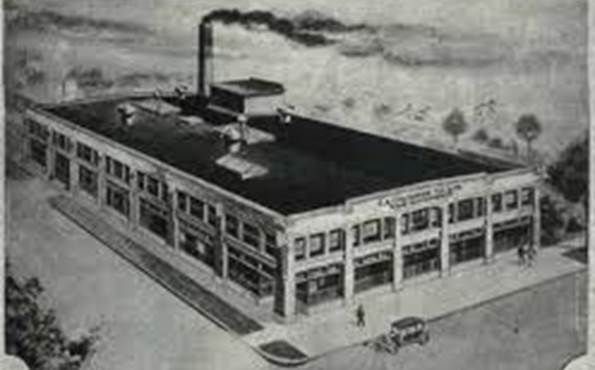

In 1904, Frank Holton & Co, relocated to an entire floor at 107 W. Madison. It formally incorporated and construction of the first 15,000 square feet of the Chicago factory and store on Gladys began. The first half of the factory opened in 1907 and the remainder in 1911. The completed Chicago factory, as it looked when fully expanded is pictured at right. Like the factory, the market for band instruments was exploding at the time, much as had been the case following the Civil War, when veterans who had experienced bands in almost every Northern, and at least a third of Southern regiments, formed town bands across the United States.

The concert band had been central to popular music in the last decades of the Nineteenth Century competing with operas for audiences and fame. Groups such as the Gillmore Band, the Sousa Band and Arthur Pryor’s Band achieved superstar status. However, the new century would bring the dawn of swing music and by the late teens, the jazz sound. This music was as uniquely unsuited to the tonal character of the cornet as it was suited to the directional nature and carrying power of the brasher trumpet. Holton’s first trumpet design, which dates to the beginnings of the company is embodied by the 1905 shown below.

In 1911, Holton transformed their trumpet into a very modern horn as shown by the 1911 below.

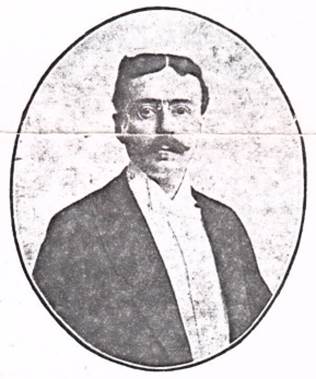

From 1907 into 1913, Ernst Couturier, considered by many to be second only to Herbert L. Clarke as cornet virtuoso and superstar of that genre of popular music, had been the leading spokesman for the Company. He served as road-man and promoter, and was responsible for significant growth in Holton sales. In 1913 he left the company to pursue production of his 1913 patent for a continuous conical bore cornet. After his first venture in partnership with JW York, the York Couturier Wizard Model, did not meet his expectations, he bought the failing William Seidel Band Instrument Company, moved it to LaPorte above a large garage and began production of a full line of pure conical bore instruments in his own name. His eyesight failed in 1923, and the company fell to receivership and purchase by Lyon & Healy within months. A genius in brass design, Couturier died in an asylum in 1950.

But Couturier was not replaced at Holton by another cornet artist. Perhaps the early jazz clubs of Chicago are what prompted the Frank Holton instead to choose a fresh-off-the-boat Austrian trumpeter who had landed a job in the Boston Symphony his first week in America, Vincent Bach. Another leading promoter of Holton was a trumpeter already, Gustav Heim, and Bach’s first job was playing alongside Heim in Boston. Heim quickly saw to the provision of a 1914 LP Holton trumpet for Bach, who arrived in Boston without one. Bach was soon featured as a leading promoter and is shown below with the 1914 Holton in this Boston Symphony publicity photo.

Bach had been born in Austro-Hungary in Baden bei Wien in present day Austria in 1890. His step-father was determined that Vincent Schrottenbach would make a name in the rapid growth of industrialization in Europe at that time. Vincent was sent to what translates as “machine builder school” from which he graduated by age 20. Labor unions being unknown to central Europe at the time, there was no division of labor between mechanical engineering (or machine design) and skilled trades. Bach was trained in a broad range of technology from delicate machining through metal working and heavy construction. He also had the fundamental education necessary for engineering. This could have put him in harm’s way when inducted into the Austro-Hungarian military, except that he had also been playing the traditional imperial highly-conical rotary valve trumpet since age 12 and was accepted as a military musician.

After leaving the military, he defied his step-father’s wishes and began a solo career touring Europe as a virtuoso cornetist. This brought him to England in June 1914 where, amid great success, events forced a radical change in his life. In Sarajevo, Arch-Duke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and as war followed, he found himself, as a reserve member of the Austrian military, also a public figure on enemy soil. He booked passage to New York, signing the manifest as Vincent Bach to elude pursuit.

The Bach Stradivarius trumpet is said to be based on the Besson that Bach brought with him to New York. However, Bach’s account of his first performance in what turned out to be a burlesque house, indicates he had a Besson cornet, not trumpet. And while all perinet valve trumpets to some degree, and the Stradivarius in particular, are similar to the Besson, there is far greater Holton DNA observable in the Strad.

Bach did not stay long with Holton, or out of the war. In 1918, he was drafted and served as a bandmaster and bugle instructor in the US Army. After the war, Bach set up a lathe in the back of the Selmer Music store in New York and began his first business. The kindnesses of the Selmer stores at this time in his life were later cited as the reason Bach elected to sell his company to Selmer in 1961 in spite of higher bids from others.

By 1916, Frank Holton’s personal finances had transformed from the near desperation of 1900 to a comfortable income and he bought a small farm in Elkhorn that would be his retreat and recreation for the remainder of his life. At the same time, the Chicago plant had expanded to fill every available inch of the property and a house across the street. He realized the company needed a new home and George Renner immediately began lobbying in Elkhorn to incentivize Holton & Co. to move there.

The 2000 citizens of Elkhorn raised $43,000.00 and contributed tremendous volunteer labor to make the 80,000 square foot brick facility a reality. In October of 1918, the entire contents of the Chicago plant were loaded onto train cars and moved to the new plant. The 6 acre facility was provided free to Holton in exchange for committing to a total payroll of at least a half million dollars over the following seven years. With exponential sales growth, this had seemed an easy challenge in 1916, but by 1918 the situation had changed.

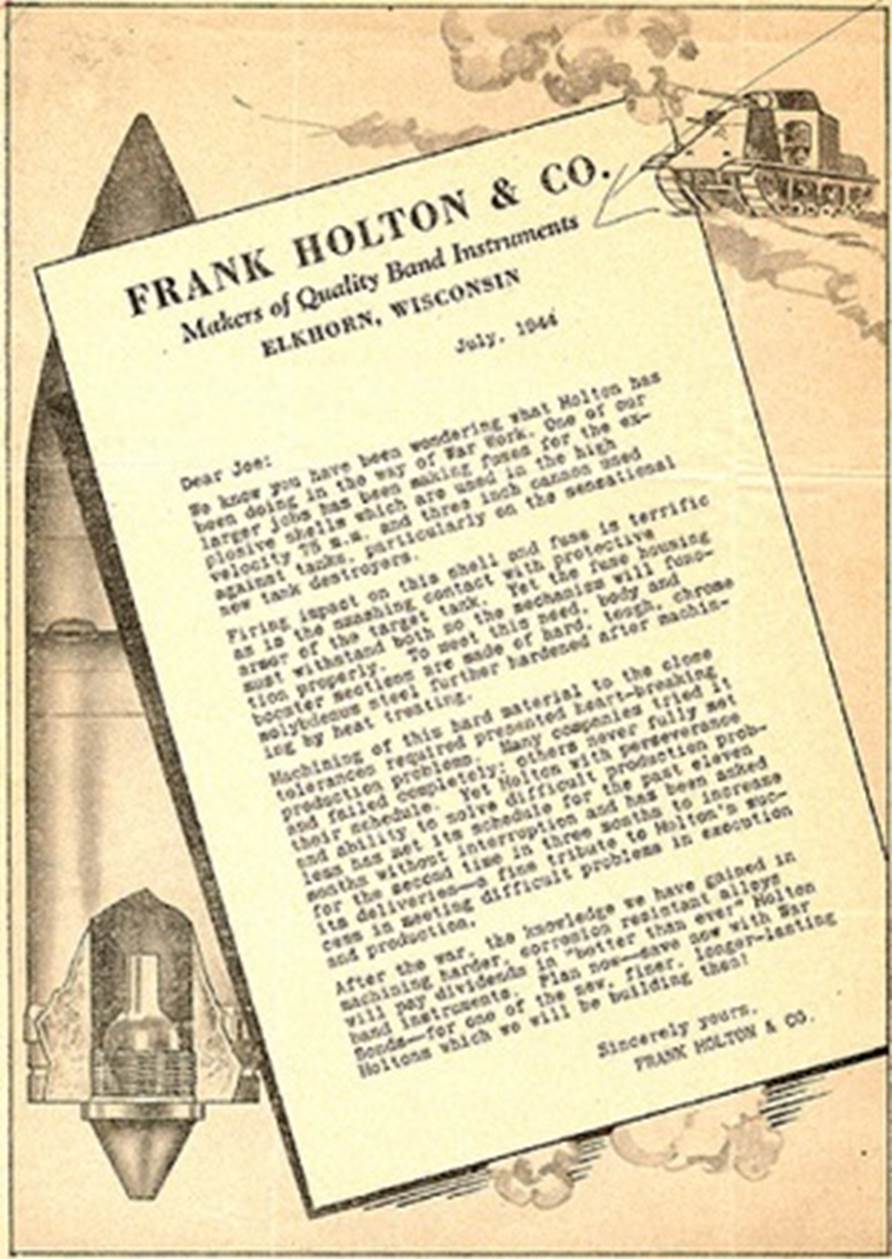

In the summer of 1917, popular outrage over the 1915 sinking of the liner Lusitania manifested into American entry into World War One. By fall of 1918, not only was brass hard to come by, as it was needed for shell casings, but so was young labor to train and then operate the new plant. Holton recalled 1916 - 1919 as the hardest time of his life, even harder than the cash-strapped first 3 years of the business.

With labor and material shortages holding down production, Frank Holton battled throughout the war just to prevent the government from shutting down the plant by cutting off its materials. He was required to make production quotas, and at times had to be very creative to do so. Once in Elkhorn, that pressure amplified. To recruit workers, Holton invested in building a neighborhood of homes. Unfortunately, the city was unable to complete the sewers to support these and in the fall rains, the basements all flooded. Diverting manpower from the plant to pump out flooded homes, Holton then had to arrange the construction of temporary sewers and pits with his own resources. Only in the last month of 1919 was Holton able to relax as the wartime pressures lifted and he realized that it had actually been a good year for sales. That fall, his new experimental workshop, where he was spending much of his time as a form of stress relief, would produce a prototype that two years later would evolve into the paradigm altering Holton Revelation Trumpet. Below is a pre-production run example from December of 1919. Note that the original Revelation did not feature reversed construction.

Following World War One, the American economy and instrument sales boomed. The Holton Company saw sales increase steadily and business prospered allowing the payroll to exceed the agreed target in only half of the time allotted and securing the deed to the plant. Upon arrival in Elkhorn, Holton had merged the factory band with the town band that dated back to the start of the Civil War. Among the featured acts with the band was a “Child prodigy” (he was 14) named Reynold Schilke. Shilke, who learned instrument making and gunsmithing in the Holton plant, became an accomplished acoustical scientist as well as trumpet designer and aided Elden Benge in getting started. Schilke would later design the famed Martin Committee trumpet, which many mistakenly see as the beginning of lightweight reversed construction trumpets, based largely on the later Revelations that he played as a member of the Chicago Symphony. He ultimately founded Schilke Music Products, which became a supplier of artist-level, hand built trumpets as well as the leading manufacturer of brass mouthpieces.

Holton grew continuously from 1818 until 1929. During this time, Holton expanded on a theme that began with an unofficial dubbing of the 1906 designed New Proportion Long Model Cornet as the “Couturier Model”. With Couturier’s departure, the design had changed and the first official artist-linked model had been the Holton-Clarke Cornets. A New Proportion is at left and a Clarke at right below.

In 1926, Holton built a number of second generation Revelations modified to the specifications of Benjamin Klatzkin. This included not using reversed construction. While not a huge success, it did sell a respectable number of copies for a horn that was only mentioned in passing within an endorsement letter published to promote the Revelation family. A Klatzkin model is shown below.

Benjamin Klatzkin was born in Russia November 26, 1884, and emigrated to the U.S. in 1904. This was the same year Gustav Heim emigrated to St. Louis to join his brother there – and began playing in the Choral Symphony Society.

He first worked at the Republic Theater in New York City in the 1910s. Then, as principal trumpet of the New York Philharmonic for six seasons, 1914-1920. Klatzkin then went to the Minneapolis Symphony as Principal trumpet 1921-1923 under Emil Oberhoffer, also working there as conductor of the Minneapolis Municipal Band. From 1925 through 1931, Klatzkin was Principal trumpet with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and was then appointed Principal trumpet of the San Francisco Symphony for twelve seasons 1931-1944 (34-35 was cancelled).

Benjamin Klatzkin left San Francisco after a conflict with conductor Pierre Monteux.The orchestra had been regularly recording extensively. It was an economical undertaking because in San Franscisco, the union scale applied to all performances instead of having a premium for recordings as would become commonplace across the nation. Benjamin Klatzkin informed Monteux that he expected to be paid a recording premium as other artists were elsewhere Monteux replaced him with Charles Bubb, the Assistant Principal, for the recording. Bubb then made a mistake during the recording, and recordings were not post-engineered in those days. Bubb was upset and apologized to Monteux. According to the story, Monteux told him everyone knew he played superbly, and would believe that it was Klatzkin's error. Monteux promoted Charles Bubb to Principal trumpet, a second insult which lead to the departure of Benjamin Klatzkin. After San Francisco, in the 1945-1946 season, Klatzkin went back to the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he stayed two seasons 1945-1947.

Herb Alpert’s first teacher was Benjamin Klatzkin. Alpert co-founded A&M records and achieved great success as lead with the Tijuana Brass. .San Francisco Symphony trumpet Edward Haug was another Klatzkin student. Donald Reinberg, who studied with Klatzkin while young, soloed with the San Francisco Symphony at age 15 while continuing his studies with Earl Murray, conductor of the San Francisco Ballet - and another Klatzkin student. University of Michigan trumpet instructor and principal with the Chicago Civic Orchestra and Minneapolis Symphony, Pattee Evenson was a student of not only Klatzkin, but also Edward Llewellyn, Harry Glantz and Max Schlossberg.

Benjamin Klatzkin died in Los Angeles on April 13, 1965. Klatzkin model trumpets are almost as common as the Holton Jazz Hound, a .423 bore Revelation built 1925-31 (below), though they are both quite rare.

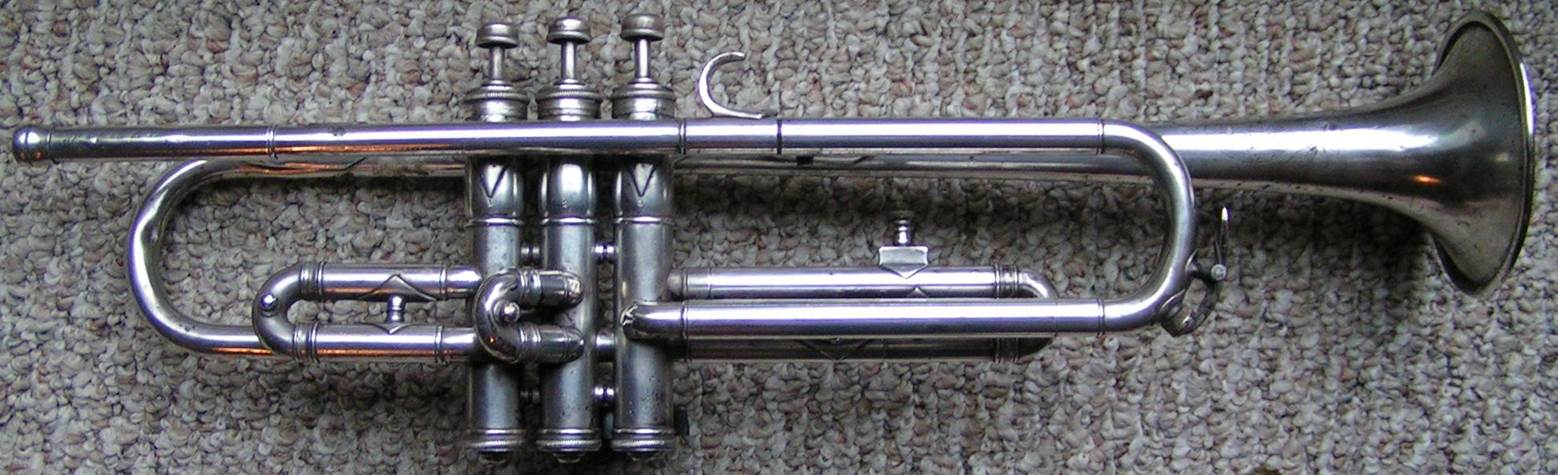

At first, Frank Holton saw the onset of the Great Depression as an opportunity, and purchased the former Couturier operations from Lyon & Healy to use for production of a new student line, the Holton Collegiate. After several years, Holton’s sales had slumped with the rest of the American business community and, with excess capacity in Elkhorn, he had no choice but to shut down the LaPorte facility and consolidate Collegiate production in Wisconsin.

Holton also expanded the artist-linked trumpet models with the .485” bore Don Berry model and the Gustat model which foreshadowed the Revelation Model 48. Neither saw many units sold and were all out of production by 1932. The one great success of the artist-linked models was the Llewellyn model, named for Holton promoter, and record-setting salesman, Edward Llewellyn (at left). The Llewellyn model is remarkably common nearly a century later despite only being built 1928-1931. The Llewellyn Model (below) is visually indistinguishable from the second generation Revelation trumpet, but has a subtly unique bell and leadpipe design.

Llewellyn’s father James had been 2nd trumpet of the Chicago Symphony 1902 to 1907 and was the first non-German trumpeter there. Edward built a career as a cornet virtuoso first, soloing 76 times at the 1904 World’s Fair alone. Taking on manager duties in 1925, he held the Chicago Symphony post from 1912 until 1933 when dentil problems forced his demotion to 3rd and replacement by Elden Benge as principle. He was killed when loose pipes from a truck came through his windshield a couple years after.

While the Holton Don Berry model may have sold few copies, it built on a trend that began with the first Revelation and progressed through the second generation and then the Llewellyn. This was the emergence of a new design of trumpet with playing characteristics quite different from the “traditional” style trumpets that would later become tied to the early-Holton inspired designs of Vincent Bach.

What was unique about the first Revelation trumpet was its structural openness. This did not really translate to much sense of open blowing to the player, but it was more responsive and flexible than the other traditional, heavily braced and trimmed trumpets common at the time. With the second generation, reversed construction, used on the first King trumpets and many cornets back to the first models, was added to the design reducing leadpipe turbulence, and thus resistance, creating a more open blowing feeling. The chief modifications to that second generation then embodied in the Llewellyn models were to adjust the taper of the leadpipe and to reduce the mass of the bell itself. This gave the Llewellyn a uniquely brighter tone, without losing the strong core that characterized the Revelations, and added still greater responsiveness and flexibility.

The Don Berry model then took these concepts to their extreme limits for the day, reducing the horn to the lightest construction possible, while increasing the bore, which was typically .459” on a Revelation, to a staggering .485”. The Don Berry was the first true large bore lightweight open-blowing trumpet design, which, with the advent of the far less aggressively demonstrative of these characteristics Martin Committee, evolved into a separate family of trumpets that continues to the present day as a favorite architecture of studio, big band and commercial players. Below is a 1929 Holton Don Berry model.

By the late 1930s the American economy was on the mend, even if the cultural attitudes and media of the time did not reflect it, and companies such as York and Holton saw sales rebound. In 1938, Frank Holton, ill and seeing his company pulling out of the rough times, decided that at 81, perhaps a man didn’t have to go to work every day anymore. He sold the company, but not to anyone, rather to Fred Kull, a trusted employee who would continue to run the firm as Holton intended. Frank Holton passed away 4 years later on April 16th, 1942. Kull died Dec. 7 1944 and was succeeded by his son Grover.

Just as the company was returning to solid profits in a growing economy, World War Two struck in December of 1941. The existence of the Holton Military Trumpet built in December 1941 by adapting a Model 48 Revelation with standard construction tuning slide and a pinkie hook above strongly hints at an attempt by Holton to convince the government to allow them to produce instruments for the expansion of the military. That did not happen. The company was converted to war material production under the Defense Plant Corporation umbrella.

In late 1945, the company was freed from government control and Holton designers had used the war years to prepare an expanded and modernized product portfolio. Holton had engaged in a variety of experiments in 1937 and 38, but by 1939 had launched several new and modern models. In the post war restoration, these models were continued and supplemented by additional variations. In trumpets alone, Holton offered the Model 45 as both a reversed construction Revelation and a standard construction, braced, De Luxe Model (shown below). The same was true for the Model 48 combination of bell and leadpipe, which is what the model number identified uniquely.

Out of the 48 De Luxe, Holton launched the Model 49 Stratodyne with a unique lightweight one piece rose brass bell – though the first examples were yellow brass. There was a Model 51 large bore version and the Model 47 Symphony all in production together by the end of the decade.

In cornets, as with other instruments, Holton also produced state of the art instruments in the mid century such as the Holton Model 25, which had developed out of the Revelation Cornet first released in 1914. One of the Holton Stratodyne models also used this design. This unique wrap was copied in the King New Professional Long Model and the Olds Special and Studio cornets among others. A 1927 model 25 is below.

Other instrument lines saw similar expansion. These models would be built for the next 20 years until the economic climate began to adversely affect the business model that began in 1898.

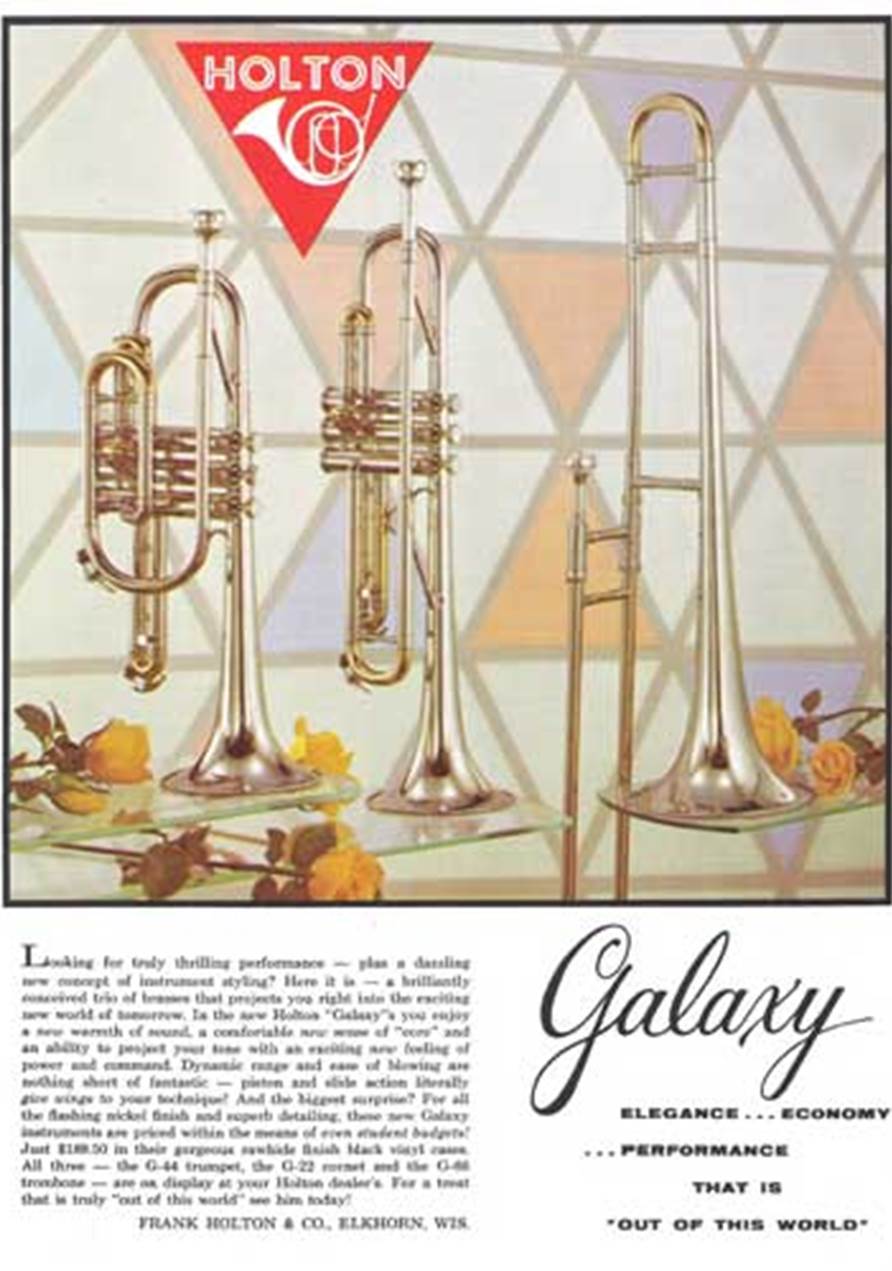

From 1962 through 1965 the Leblanc Company negotiated the acquisition of Frank Holton & Co. As soon as the first hints of takeover began, Holton started introducing new lower cost “professional” instruments, but the reality that there is no such thing as cheap quality doomed most of those products, -the remarkably well engineered Galaxy line being an exception.

In 1965, Leblanc took full control, changed all of the model names, and refocused product development from innovation to imitation. The product development work would shortly move from Elkhorn to the Martin facility in Elkhart, which Leblanc also purchased.

The history of Holton from 1962 through the 2008 closure of the Elkhorn plant and conversion of the Holton name to a stencil on Conn-Selmer products produced at Eastlake Ohio would be one of mergers, buy-outs, cost cutting, imitation of other’s designs, and artist-linked specialized products. Just one of those projects, the Farkas French Horn, would continue as a design after 2008 but be built in Ohio.

Following the merger, the Holton instrument identifications all changed. In trumpets, first there were the B- designations and then the T-. The instruments themselves became lighter, shriller, and used a different alloy for the brass. Artist associations were stressed as a mechanism to drive sales, though as was demonstrated by Leonard Falcone pulling out of the Holton Falcone Model baritone project when Leblanc project managers would not authorize the costs associated with meeting his performance requirements, the driving design criteria remained cost.

There were many such projects ranging from the Ellis quarter-tone trumpet, more of a physics project than a commercial product, to the student grade Courtois-designed, and perhaps built, Al Hirt models such as that above, to nine separate models within the T-30# series bearing the Maynard Fergussen name that actually became Holton’s most popular product under Leblanc, such as this T-304 below.

Existing professional models were sometimes propped-up by linking them to major artists after the fact. Such as the T-200 Bud Brisbois or the T-100 Symphony becoming the ST-100 Dave Stahl in the mid-70s. The most interesting incarnation of that model however was the adjustable-gap receiver T-100X, which was a largely new design by Larry Ramirez working with Warren Kime. An example is below.

This is not to say that there was not a serious orchestral offering from the Holton Company during the Leblanc period. The Holton Phillips Tuba was a respected design and the Farkas french horn became the standard against which all others were compared for many years. Recognizing that the T-10# line of Conn Constellation imitation trumpets was not at a top professional level, Holton first introduced a remake of the Model 47 Symphony in the T-747 shown below. This model, however, was built with modern Leblanc components and a Leblanc bell taper, which produced results similar to the T-100s.

Recognizing their inability to design trumpets of this type, and reflecting a realization across the product design organization in 1981, a team including Jim Stella, who would one day head operations for Getzen in Elkhorn, surreptitiously play-tested and then bought the best performing Bach Stradivarius 37 they could find at a local music store. Stella dismantled the horn, it was measured in detail, and the specifications formed from that were the design of the new Holton T-101 Symphony. A Bach 42 bell clone was then used for the new T-102 and a 72 bell for the T-103. A T-101 Bach Strad clone is below.

There was also a T-105 model developed from the T-101 as a lightweight. In 2000, Holton released a Millennial Edition trumpet, the T-2000, and chose the T-105 as the model to be so dubbed, with the addition of some very obvious gold plate accents. The T-2000 is pictured below.

Of course, like all band instrument companies, the student market was key to success in the later 20th century. The Collegiate evolved several times and became the T-602 family under Leblanc. Below are an original Collegiate 172, and its last descendant, a T-602.

Frank Holton was firstly an artist on trombone, and the first Holton promoter. Holton sales literature from the 1920s noted that Holton always kept a trombone at his desk to play for guests and promote his products. From the earliest days of his company, he leveraged his professional relationships with fellow prominent musicians to secure long lists of top name endorsements for his product. Additionally, several of the artists worked as a part of the company.

The Frank Holton Company embodies the story of American business. One determined entrepreneur, doing whatever it takes through hardship and set-backs to realize a vision of quality and innovation in his chosen field. It further embodies the full life cycle of success, imitation, investor desires ultimately overshadowing product concerns, decline, cost-cutting and consolidation, acquisition, and eventual disappearance into at best a role as a name on a conglomerate’s product that bears little resemblance to the founder’s ideals. The Holton Chicago plant is a vacant lot and the Elkhorn plant stands vacant and for sale as of 2014, but certain Holton instruments still enjoy a loyal following among children and grandchildren of those who first played them. Holton’s design legacy lives on in hundreds more through Bach, Schilke, and Yamaha.